Earlier this year, I went to the blockbuster Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350 at London’s National Gallery.

It was breathtaking. A truly once-in-a-lifetime experience.

It brings together paintings in both the National Gallery and The Met (as well as many other places) to narrate a great tale on the rise of painting in Siena over this period. Probably the best collection of mediaeval painting assembled in any one place in my lifetime. Not just the paintings but also the beautiful selection of textiles from the Middle East represented in some of the clothes depicted were fascinating. Such a nuanced and insightful perspective on art history through the historic period of global trade.

The best parts were the uniting of works and altarpieces which had not been seen together for hundreds of years - and unlikely to be reunited again in my lifetime. Not to mention some masterpieces - e.g. Duccio’s Annunciation.

What is really exciting about this exhibition is its dive into some art history discussion. This is something I love, but don’t often experience.

Rating: 5/5 ★★★★★

I have condensed my write-up into blocks devoted to each master, over two blog posts.

✲

Some noteworthy points of art history raised in the exhibition vis-a-vis Siena:

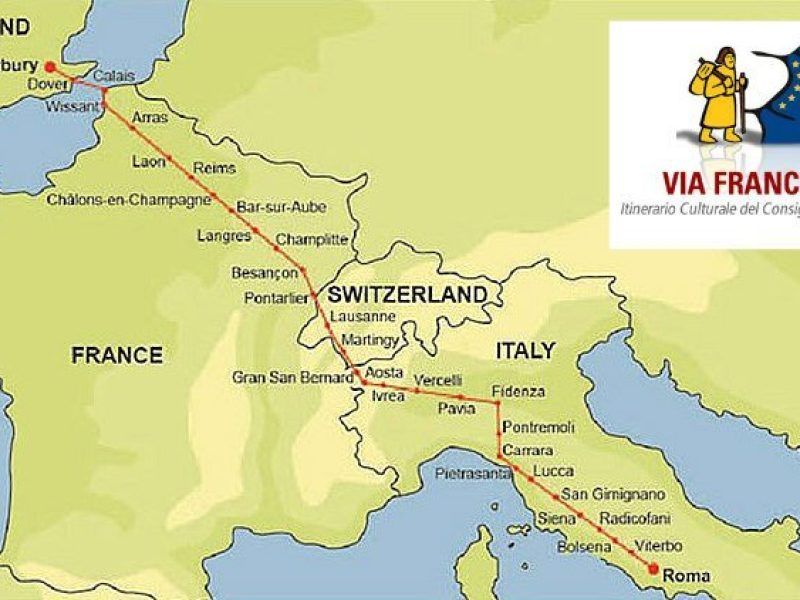

- Between 1300-1350, it was a major city in that area of Italy. This is because of the pilgrimage route first followed by Archbishop Sigeric from Canterbury to Rome in AD 990. This meant that Siena was extremely well-placed for the merchants and traders (to and from Champagne and Flanders etc.) as well as the Papacy’s influence (seated in Rome) between Southern and Northern Europe.

- That pilgrimage route and tradition was a very important source of patronage for the arts - e.g. goldsmiths. Pilgrims would buy bits-and-bobs of devotional significance in Siena and then bring them back home up North.

- Siena was a city dedicated to Mary, Mother of God – leitmotif of the exhibition. (She was considered to have intervened to save Siena from Florence in 1260 at the Battle of Montaperti).

- Siena (for this period, 1300-1350) enjoyed a period of stability in its (slightly) representative government which gave rise, as the exhibition would describe it, to “the rise of painting”. A true bourgeoning. It flourished again in the 15th century. But, in 1550, Siena was conquered by the city of Florence. As part of the conquest, the art of Siena had begun to be forgotten. Giorgio Vasari has to absorb some of the blame here too.

- The city of Siena experienced the devastating event – the Black Death.

- The exhibition makes clear that Simone Martini’s style became influential to the International Gothic of the courts of Northern Europe, extending to the glorious “Wilton Diptych” of England.

✲✲✲

Part 1 - Introduction & Duccio

Duccio was the formative star painter of Siena. What’s amusing is that there are (apparently) records of his misdemeanours - e.g. “unruly behaviour” and unpaid taxes (haha!). Yet, his Maesta is one of the touchstones of Western painting.

Among Duccio’s many gifts is his ability to create coherent, emotionally engaging images that draw on disparate sources.

Duccio knew the Byzantine art tradition but was also well-placed wrt Northern European Gothic art.

✲✲✲

Madonna and Child by Duccio (The Stroganoff Madonna) (1290-1300)

According to the exhibition, it is Duccio who began the tradition of Italian Renaissance depictions of the Virgin Mary and her baby with touching maternal gestures and expressions. Mary lovingly holds her little boy. Baby Jesus responds to her caress - as all babies do - by pulling on her veil and touching her wrist with his toes. Mary’s tragic expression reveals her knowledge of her child’s future suffering.

There is a 3D parapet.

✲✲✲

The Virgin and Child Enthroned with Angels by Duccio (1290-5)

Beautiful.

An object of private prayer. The Virgin, the Queen of Heaven, on a decorated throne surrounded by six angels.

Again, we see the emotional attachment of mother and son. Christ clings tight to Mary, one hand round her neck, the other stroking her fingers.

This is a cousin of The Rucellai Madonna at the Uffizi.

✲✲✲

Triptych: Crucifixion and other Scenes by Duccio

The earliest of Duccio’s surviving triptychs.

Mother Mary appears in all but one of the scenes.

✲✲✲

The Crucifixion by the “Master of Città di Castello” (1315-20)

This artist, whose name is lost, was one of Duccio’s most talented followers.

It seems he was inspired by some of Duccio’s interpretations from the Maesta. Striking is Mary Magdalene stretching her arms to the heavens.

✲✲✲

Triptych with the Crucifixion, Saint Nicholas, Saint Clement and the Redeemer with Angels by Duccio (1311-18)

A very intense central panel - a paroxysm of confusion and grief. Soldiers and onlookers gesticulating wildly or recoil in horror.

I love the Saints and their robes. Attention to detail and delicacy.

Mourners gather to support Mary’s fainting body.

I was curious about the origin of Mary’s fainting in depictions of crucifixions. I wondered whether it started with Duccio. After some research, it seems to have originated slightly earlier in 1260, by Nicola Pisano:

... panels from the Pulpit of the Baptistery of Pisa. The panel of the Presentation in the Temple (left). The Crucifixion panel (center) depicts more classically-inspired figures, here the figure of the grieving Virgin Mary represented falling into the arms of the other women ... , adds something totally new to the iconography of this scene, something more “human” than “divine”.

✲✲✲

The Virgin and Child with Saints Dominic and Aurea by Duccio (1300-1305)

I have already blogged about this particular triptych at the NG.

It is astonishingly touching with a sense of melancholy. I love it. The ultramarine is astounding.

Duccio built on techniques and iconography to create powerful paintings evocative of empathy and awe.

✲✲✲✲✲

Part 2 - Duccio’s Maesta

The exhibition then moves to a magical moment of Sienese art history.

In 1311, a huge painting of the Virgin Mary was welcomed to Siena Cathedral. That Maesta was commissioned from Duccio for the high altar in honour of the Virgin, Siena’s patron. The altarpiece front was the Virgin seated. At the back, a sequence of scenes from Christ’s life.

This exhibition reunited all eight of the surviving panels from the back predella (and two from the front) for the first time since they were sawn in half (in 1771) and sold separately some 250 years ago. The exhibition argues that Simone Martini, Pietro and possibly Ambrogio worked with Duccio on his Maesta.

✲✲✲

The Nativity with the Prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel

✲✲✲

The Annunciation

✲✲✲

The Temptation of Christ on the Temple

✲✲✲

The Temptation of Christ on the Mountain

✲✲✲

The Calling of the Apostles Peter and Andrew

✲✲✲

The Wedding at Cana

✲✲✲

Christ and the Woman of Samaria

✲✲✲

The Healing of the Man Born Blind

✲✲✲

The Transfiguration

✲✲✲

The Raising of Lazarus

✲✲✲✲✲

Part 3 - Simone Martini

Following the death of Duccio in 1319, Simone Martini (1284-1344) became Siena’s foremost painter. As the exhibition explains, his name appears on almost all civic public records of commissions at the time.

Not only did he achieve an incredible decorative power to his art, but he was technical virtuoso. As the exhibition points out, his draped clothes suggest a link between Siena and the French gothic. Indeed, not only would he be working in Angevins (for the French royal family), but eventually at the papal court at Avignon.

✲✲✲

Christ on the Cross by Simone Martini

Wow. Such a powerful painting. As Harvard write:

The jewel-like image shows the figure of the crucified Christ alone, heightening the beholder’s empathy and engagement with his suffering. This delicate painting may have been made during the final period of the artist’s life, which Simone spent in the papal court at Avignon in France.

Saint John the Evangelist by Simone Martini

The Palazzo Pubblico Altarpiece by Simone Martini

These panels were probably made for Siena’s government headquarters, the Palazzo Pubblico.

Simone Martini’s attention to detail is masterful - hair minutely depicted, vital flesh tones, fabrics etc.

✲✲✲

Old Saint, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Peter and Young Saint with a Book by Gano di Fazio

✲✲✲

Diptych with the Annunciation and the Assumption by Francesco di Vannuccio

The exhibition uses this portable diptych to illustrate the long shadow that Simone Martini cast over artists in Siena. The exhibition explains the inspiration was probably Simone’s Annunciation at the Uffizi:

✲✲✲✲✲

Part 4 - Simone Martini in Avignon

In 1309, the court of the Popes settled in Avignon, Southern France. At the time, the Papal court were especially attracted to Sienese paintings. Thus, in the first half of the 14th century, the city became home to one of the greatest communities of Sienese painters and goldsmiths outside Tuscany. Foremost among them was Simone Martini, who left Siena after 1333 and spent the final decade of his life in Avignon.

Siena’s fortunes waned in the second half of the 14th century, following the bubonic plague. But the city’s artistic legacy would be tended by generations of artists beyond Siena.

The Orsini Polyptych by Simone Martini

Christ Discovered in the Temple by Simone Martini

In the Gospel of Luke, the twelve-year-old Jesus is found in the Temple in Jerusalem by his parents.

Here he seems to be admonished by his mum, and he’s irritated at being told off (😁) !! As Sara McKee writes:

The panel portrays a very rare subject. It appears to show Jesus saying goodbye to his parents, Mary and Joseph ... Unusually for the period, it represents an involved human situation, a difficult family issue not yet resolve.

✲✲✲

The Belles Heures of Jean De France by the de Limbourg Brothers

The exhibition points to the Sienese influence on the de Limbourg brothers.

In The Belles Heures (“Beautiful Hours”) prayer book:

In this striking Lamentation, several motifs - like the woman tearing at her hair, Saint John the Evangelist covering his eyes, and Mary Magdalene seen from behind crouching over Christ’s feet - are adapted from Simone’s Orsini Polyptych, which their patron may once have owned, and Pietro Lorenzetti’s frescoes at Assisi.

✲✲✲

The Wilton Diptych

The exhibition explains that the Wilton Diptych is an example of the international impact of Sienese art. The kneeling king is presented to the Virgin and Child.

Most likely painted in northern Europe, but the technique is Italian. The sgraffito technique of scratching away paint to reveal gold leaf. Used on the splendid textiles - a characteristically Sienese effect.

Yu are so lucky to have seen these paintings. Some I've seen before only in photos but they are all good in their own way.

ReplyDeleteA wonderful exhibition for art connoisseurs.

ReplyDeleteAn amazing and beautiful exhibition. Thanks for sharing.

ReplyDeleteOlá. Espero que estejas bem. Agradeço sua visita e comentário. Parabéns pela exposição. Obrigado por nos trazer. Novos amigos sempre serão bem-vindos. Fatam poucos dias para a primavera na maior parte do Brasil. Sim temos verão e inverno, por sermos cortados pela Linha do Equador. Grande abraço carioca do Rio de Janeiro.

ReplyDeleteInfelizmente não consegui, ser um novo seguidor do seu Blogger, coisas do Google.

ReplyDeleteLiam ... a beautiful post.

ReplyDeleteYou shared and showed this exhibition so well.

Thank you.

All the best Jan